#15: Why development took so long

This post was originally written in November 2022

I started making Curious Fishing in October 2016 and finally released it in September 2022, a total of 72 months inclusive, or 6 years. That’s a very long time to spend making anything, let alone a small free puzzle game. What took so long? I’ll first discuss it in general terms (qualitative), then do a deep analysis of the source control commit history (quantitative). Contain your excitement, there will be graphs.

First I want to make it clear: I’m super happy with the game and the reception it received! But after spending 6 years on something, I think it’s useful and interesting to reflect on that. This is less a postmortem of the game and more a postmortem of the process of making it.

Life happened

Over the course of those 6 years I’ve:

- Had 3 different computers

- Had 3 different full-time jobs (and am about to start a 4th)

- Changed apartments 6 times across 4 cities

- Had 3 romantic relationships

- Had personal health issues

And of course there was an extremely dangerous, saddening and disruptive global pandemic in the latter half.

Curious Fishing was a personal project, worked on largely during evenings and weekends (this is shown very clearly in the commit analysis later). I definitely worked myself too hard at times, but was generally responsible in setting this project to one side when my time and energy were needed for other more important life commitments. There are many long breaks where the game wasn’t worked on at all, but I always came back to it eventually once I had the capacity and motivation again.

One aspect of motivation was creative satisfaction in my full-time job as a games programmer. In the time it took me to make this one game start to finish I went from Junior to Senior and worked on many different projects professionally, including more than a dozen games across a dozen platforms, 5 of which launched and 2 of which are still under development. There were times where I was creatively fulfilled enough by my regular job that I felt no need to work on something in my own time. There were other times where I was so dissatisfied with my job that I had no energy or motivation for my own projects. Unfortunately the latter occurred more often and for much longer.

Scope creep

The nature of this project changed several times during development:

- Free game jam (in PICO-8)

- Free expanded version

- Premium mobile (this is when it moved to Defold)

- Premium desktop

- Free web with support for both desktop and mobile (this is what actually launched)

The shift from hobby project to commercial indie led to me taking on a massive amount of extra work, none of which was enjoyable. This increased the workload, increased the stress, and decreased my motivation. The eventual shift back to hobby project is what ultimately enabled me to finish the game, because I was able to just focus on the parts I actually enjoyed or at least had an interest in doing. In the end the final game still had a level of content and quality that I would be comfortable selling for money anyway.

The other part of scope creep is that I intentionally used the project as a way to experiment and gain experience with aspects of game development that I hadn’t seen during my regular job. This was both out of personal and professional interest, and as a way to ensure there were practical benefits from the time commitment. As a result, the amount of polish and functionality in the final game is arguably disproportionate to the size and complexity of the actual gameplay. Derek Yu, the creator of Spelunky, calls this the Loop of Polishing in his excellent article Indie Game Dev: Death Loops.

So what was the scope, in the end? Here are the major kept things I spent time on:

- Over a dozen fishing-themed puzzle mechanics, the most complex being the green fish that patrol around as the player moves

- 30 levels including 3 boss levels

- A playtime of around 1 to 4 hours depending on how familiar you are with puzzle games

- Lots of low-res pixel art, retro sound effects and chiptune music (all audio was created by Andrew, with specifications and feedback from me)

- Unlimited undo

- Menus: pause menu, aquarium menu that fills in as you progress, settings menu (also accessible via pause menu, so changes apply while a level is in progress), level select menu with progression unlocks, looping scrolling credits menu

- Resettable save data which tracks level progress, aquarium completion, settings, and the minimum number of moves used to complete each level (this bonus feature is revealed after completing the game, to add replay value for trying to optimise your solutions)

- Keyboard, mouse, gamepad and touchscreen input support

- Pixel-perfect rendering at any resolution, with a virtual handheld console case reminiscent of a Game Boy in portrait mode or a Game Boy Advance in landscape

- Player customization of avatar, case palette and case button layout

- Fully localized into 12 languages, including support for non-Latin alphabets and right-to-left directionality

- 13 detailed devlogs at the time of release, with 2 more since then (including this one)

- A detailed and heavily stylised itch store page

- Design planning documents and kanban board task management with a couple hundred tickets

That’s a lot!!! And here are the major things I spent time on but didn’t keep:

- Considerable admin setting up products on the Google Play Android and Apple App Store iOS storefronts, and understanding the requirements and features of those platforms

- Lots of work and debugging of Android and iOS builds, the latter also requiring the purchase of and familiarisation with an OSX device, which I’d never used before

- Complex movement conflict resolution logic for a flowing water puzzle mechanic

- Experiments for additional levels, with the intention at one time of bringing the total to 50

Technical difficulties

I’ve not used Defold before and it has an unusual (to me) architecture centred around message passing. I didn’t have time to learn this properly when crunching to port the game for the GDC Competition (see devlog 1), meaning the foundational code of the game somewhat subverts and fights against the way the engine wants things to be done. I continued to build upon this throughout; implementing things within a single script was generally fine, but whenever I needed to communicate between scripts or manipulate engine components it was always a struggle.

I first learnt how to code using C and C++ and have spent most of the last 6 years programming professionally using C# with Unity. I’ve made a number of small game jam projects in Lua but nothing at scale until this project. I personally found Lua to be too freeform, I missed the structure that classes and strong typing provide. It’s too easy to be lazy and do things on the fly in inconsistent ways, haphazardly tack variables onto objects, or throw global variables around (intentionally or unintentionally).

One thing that was unclear to me was what version of Defold I was supposed to be using. Releases are very regular, mixing together both features and fixes. For an irregular side project, keeping up with releases took an annoying amount of time (until I abandoned doing so), and often led to subtle bugs or changes in behaviour. I prefer the clarity of the release structure that Unity, Godot, Blender and many other software projects follow, with key feature versions followed by stabilising Long Term Support versions. If you need or want the new features then you update, otherwise you stay on LTS and just receive bugfixes.

Commit history analysis

Process

This analysis of the Git repository comes with a number of caveats to understand first.

- There are a number of things that took considerable time and effort but which aren’t represented in the Git repo:

- The first three months of development in PICO-8. The Git repo only started with the Defold version of the game. From October 2016 to December 2016 the game was still in PICO-8, a platform designed around pleasant simplicity, including the fact that all assets (code, sprites, maps, sfx and music) are stored together in a single human-readable text file. I had no need or desire to complicate that. So the repo only covers from January 2017 to release in September 2022, 69 of the total 72 months of development

- The Positive Aspects tool and aspect ratio prototype. As explained in devlog 5 I created the window resizing tool Positive Aspects initially for this project, before expanding it to a standalone release. I used PA to iterate on the pixel-perfect aspect ratio scaling in a separate minimal Defold project before integrating that working prototyping into the full game. These were around ~15 and ~20 commits respectively, from April to June 2018

- Design thinking and the resulting planning documents

- A lot of admin work, including managing the kanban board for task tracking

- These devlogs

- It does include creating the itch store page as that is heavily stylised hand-written HTML, stored alongside the game

- Defold used to host project repos, which is where this one started. I had to move it in April 2021 before that was shutdown, which added a handful of commits

I also want to clarify that ‘number of commits’ is an exceedingly loose metric as a single commit might represent minutes, hours or even days of work. But this is the only metric I have, so.

I exported the commit history using the following command:

git log --reverse --date=format:"%d/%m/%Y %A %H:%M" --format=format:"%ad %an %s" > log.txt

Let’s break that down:

git logoutputs commit history--reversechanges from the default reverse-chronological to forward chronological, so the oldest commits were at the top--date=...customises the output for the date and time of each commit, using the formatting options of the Linuxstrftimefunction%dis the two-digit day of the month%mis the two-digit month of the year%Yis the four-digit year%Ais the name of the weekday%His the two-digit hour (00-23)%Mis the two-digit minute

--format=...customises what information is output for each commit%adis the authoring date, respecting the specified date format%anis the author name%sis the ‘subject’ of the commit, i.e. the commit message%Bcan be used instead of%sto get the ‘raw body’, which preserves newlines in multiline commit messages

> log.txtpiped the result into a text file instead of displaying it on the command line

Here are the first four lines of the resulting log.txt file so you can understand the format:

05/01/2017 Thursday 22:47 ConnorHalford Initial commit

05/01/2017 Thursday 22:46 ConnorHalford Initial project setup

06/01/2017 Friday 23:24 ConnorHalford 128x128 rendering

06/01/2017 Friday 23:50 ConnorHalford Exported spritesheet and set clear color

(I don’t know how or why the very first commit in Git has a timestamp earlier than the second, but that’s what it outputs. All subsequent ones are in order.)

This gave me a text file containing the commit history of the project in a standardised form, that I could then turn into a spreadsheet and start performing data operations on. I manually added a ‘category’ to each commit to tag what feature it was primarily associated with. I also changed the weekday for all commits that were past midnight, so for example if a commit were at 01:30 AM on a Saturday, I treated that as being part of the Friday’s work.

Overview

- 647 commits in total, 627 by me, 20 by Andrew the sound designer

- Subtracting merges: 640 total, 623 by me, 17 by Andrew. Work was done on a single branch for the whole development, because I only worked on one thing at a time and was working alone 99% of the time. The 7 automatic merge commits were all early on, when we both happened to be working at the same time and one person committed before the other

- In the first devlog I mentioned that I crunched for 3 weeks at the start of the Defold project in order to enter the GDC Competition, then another 3 after having won, and continued to tweak levels during the event itself:

- 83 commits in the first 3-week crunch to enter the competition

- 50 commits in the second 3-week crunch preparing for GDC

- 5 commits during GDC

- Most commits in a day: 15 on 29th May 2017 with another 13 the next day, all on early localization work

- Longest commit message:

- 665 characters / 107 words / 6 lines on 5th January 2019, for 6 gameplay fixes and improvements, especially around patrols

- 593 characters / 92 words / 8 lines on 22nd January 2020, for 7 graphical fixes enforcing consistency across assets

- Longest work day (note this is an even looser metric, using just the time between the earliest and latest commits in a single day; this doesn’t account for the unknown amount of time spent working on that first commit)

- 12h 27m from 12:58 to 01:25 on 10th February 2017, for 9 commits around level and boss designs. There were definitely breaks, but it was mostly work

- Technically the longest day is 14h 4m from 10:29 to 00:33 on 6th May 2017, for 5 commits of various graphics improvements. But most of that day was not spent working on the game, just the morning and evening

- Earliest commit: 07:37 on 2nd March 2017

- Latest commit: 02:26 on 21st July 2019

- Longest gap without commits: 261 days (~8.5 months) from 4th September 2019 to 21st May 2020 inclusive

- Knowing that there was work done in all 3 of the months of development prior to source control, 25 of the 72 months in development had no commits, ~35%, more than 1 in 3

- 22 if you factor in the Positive Aspects tool and aspect ratio prototype from April to June 2018, ~31%

- Number of unique days with one or more commits: 218. If you were to spread that over 5-day work weeks it’d be 44 weeks, so if I’d worked on the game full-time instead of on the side it would have taken (extremely approximately) 1 year instead of 6. Looking at the scope detailed earlier, I think that sounds reasonable. I do think the game benefited in some ways from the long breaks though, as it allowed me to come back to the project with fresh eyes multiple times, which is very useful when working alone. Also having a job lets me, y’know, eat and pay rent, plus working as a games programmer helps me develop useful skills and knowledge

Hours and days

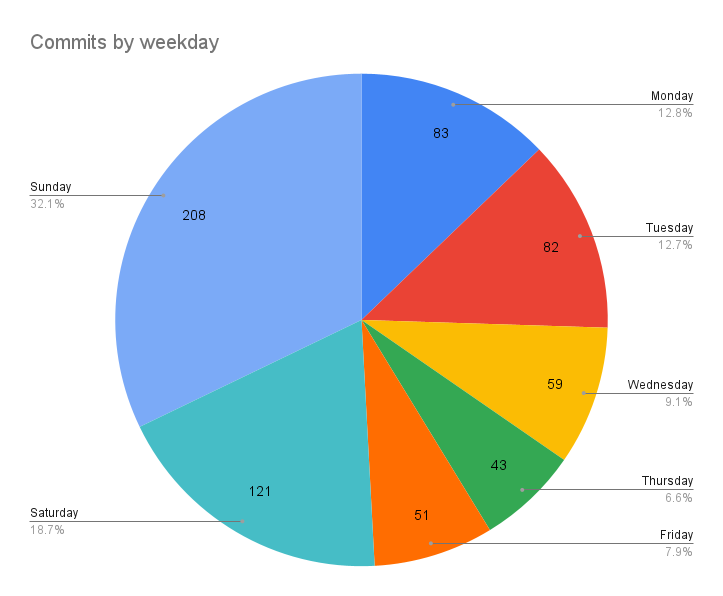

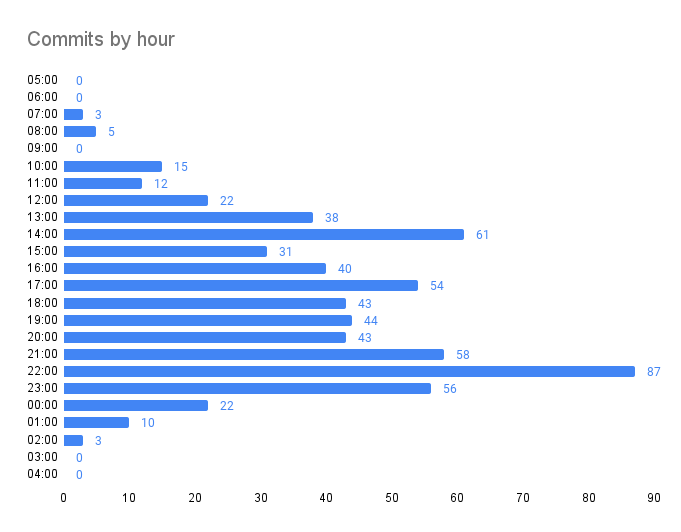

When I say I mainly worked on the game on evenings and weekends, here’s what I mean:

Just over half of all commits were done on Saturday or Sunday. I think there are more on Sunday because I would usually have a lazy Saturday morning to relax from the workweek, and because work started on Saturday would often not be completed and committed until Sunday. Momentum and energy carried through to Monday and Tuesday but fell off as the week progressed and I got tired from my job. Some weekday commits were done on days off from work; a couple of times I used some of my annual paid leave allowance to dedicate a week to the project.

Lots of interesting things here. As you can see I’m not a morning person; where possible I prefer to start working later in the day into the evening. I know exactly what the spikes toward 14:00, 17:00 and 22:00 are too; I don’t like being interrupted in something and prefer to either finish it or get it to a point where I can more comfortably pause and resume it later. As a result I often take very late lunch breaks, wanting to finish what I’ve been working on in the morning first; this is what the big 14:00 spike is as I wrap things up, and dip at 15:00 as I take a break. I reckon the 17:00 spike is similar, wanting to finish things before stopping for the day or for a dinner break, or wrapping up smaller or resumed tasks after having taken a late lunch. I would usually have dinner somewhere between 18:00-20:00, with any work started after that wrapping up in the huge 21:00-23:00 spike, or getting carried away past midnight. If I was working on the game on a weekday evening, I would tend to work 10:00-18:00 at my regular job, relax and have dinner 18:00-20:00 or 21:00, then do a few hours of work before bed.

Months and years

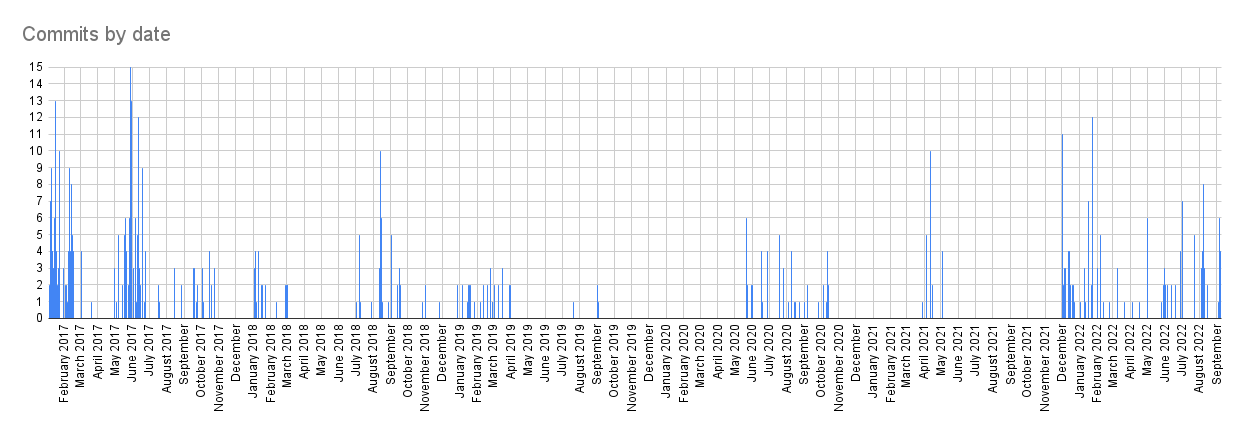

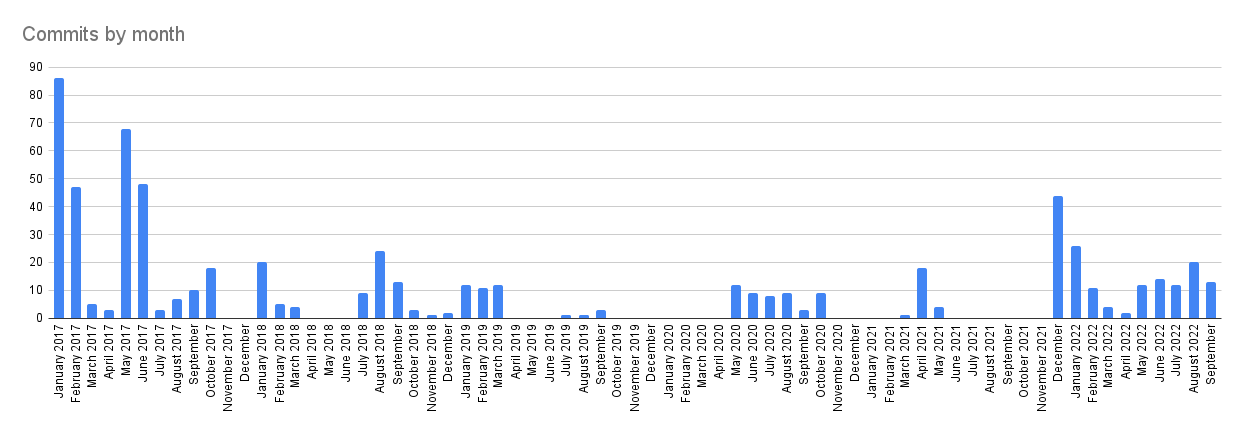

Here are the dates of all the commits, by day and by month:

You can see clearly here the multiple long breaks I took from the project when my energy and motivation were lacking or otherwise engaged. The beginning of the graph shows the crunch for GDC, the subsequent burnout, the rejuvenated drive, then the burnout again as my ambition got the better of me. Work after that tended to be at a much slower (healthier) pace. Note that the 3 month ‘gap’ April-June 2018 is when the Positive Aspects and aspect ratio prototype projects took place. The spike in December 2021 is when I knew I was starting the final push toward release and was excited and energised by that, and had lots of time off from work over the Christmas and New Year period to dedicate to the project.

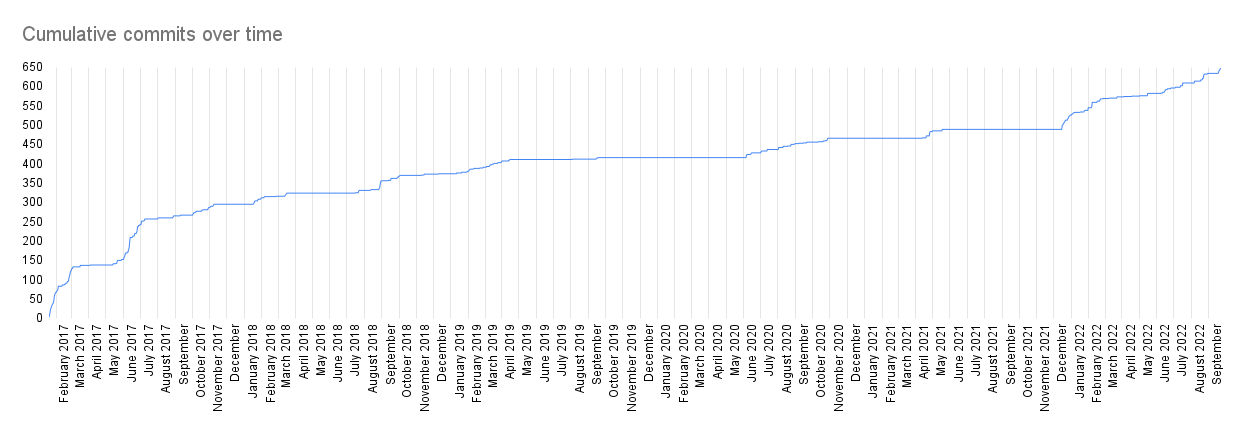

Here is another look at the same data, showing the cumulative number of commits over time. A plateau shows little or no progress, while the steeper an incline is the more rapidly progress is being made (but again the metric here is ‘number of commits’ which is only a very loose approximation of the amount of work being done). I like how consistent the progress is in the final push toward release; this graph kind of embodies my determination to finish the project. It was only ever on hold, never abandoned.

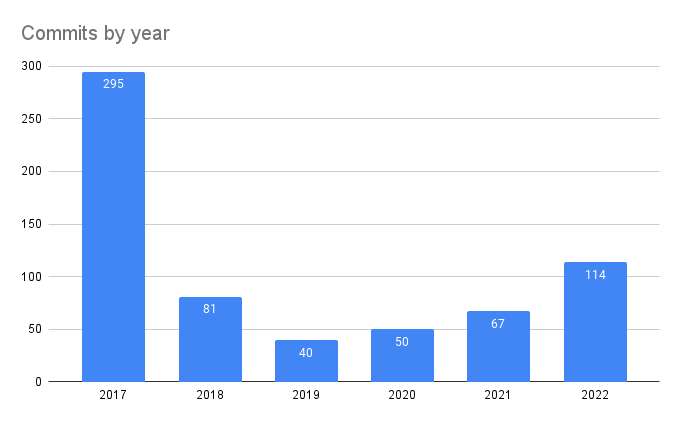

Lastly here are the commits grouped by year, though remember that the first 3 months of the project were in 2016 and not tracked under source control. The game was released in early September 2022, so there were ~3.5 months left in that year.

Categories

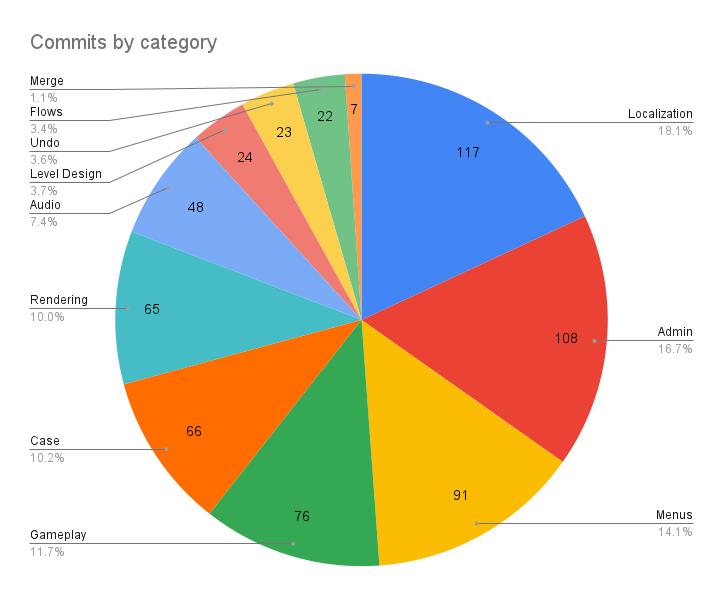

Once the commit data was in the spreadsheet, I manually went through each message and assigned a category for the area of work that commit most contributed towards. The final categories were as follows:

- Admin. Any work not part of the game itself such as Defold config, Git config, debug functionality, the itch store page, or meta operations like organising files

- Merge. Automatically generated Git merge commits

- Audio. Andrew adding his audio assets or me working on the code that uses them

- Gameplay. The core mechanics of the game such as player movement, creature behaviours, the in-game HUD, etc.

- Flows. Work on the cancelled flowing water mechanic

- Undo. Refactoring all the existing mechanics to support full undo

- Level design. Working on the levels / puzzles

- Localization. Changing assets and menu layouts to support multiple languages

- Menus. The pause, aquarium, settings, level select and credits menus

- Rendering. Visual stuff: camera, shaders, sprite depth ordering, nice animations, etc.

- Case. Pixel-perfect scaling at any aspect ratio, the handheld console layout including interactive animated buttons

The first thing to note is that the surprisingly small number of level design commits is quite misrepresentative, as a large part of the level design work was done during the first 3 months of development prior to source control, and later changes to levels were often bundled in with related changes to gameplay or rendering which were categorised separately. I gave each commit only one category, focusing on the primary topic.

Localization was the single largest category of work by number of commits, although Rendering has more if you include its Case subcategory. I found that Localization work does lend itself to frequent small commits, as I would work on one area of the game and ‘bank’ each language once it was working. So that’s a weakness of this ‘number of commits’ metric, but Localization was certainly one of the biggest areas of work in terms of time and effort too, so I think this is still pretty accurate.

A lot of the Admin category early on was configuring Defold. In the middle was debug functionality, for example when I did the final pass on the 16 case palettes I wanted to be able to tweak colours at runtime. Since the aquarium doesn’t otherwise use the d-pad, I added debug code there where up/down would cycle between the different parts of the case and left/right would cycle it through the 16 colours of the palette, with everything being logged to the console. This made it much faster and easier to experiment until I found combinations I liked. The other debug functionality I had was a cheat key (also triggered by four simultaneous touches on mobile) which would mark the current level as complete, or if done outside of a level it would mark the first 29 levels as complete so that I could easily test completing the final 30th level for the first time per save file. Towards the end the Admin category was mostly work on the itch store page HTML.

It turns out making the ‘actual game’ is quite a small part of the process. Game jams and small side projects are fun because that’s the part they focus on almost exclusively. Expanding that to a commercial level requires a tremendous amount of surrounding functionality. I think that’s a big part of why making games is hard; not only do you have to make something fun and interesting and engaging with hours of content, you also have to make a robust piece of software with a lot of functionality and good user experience.

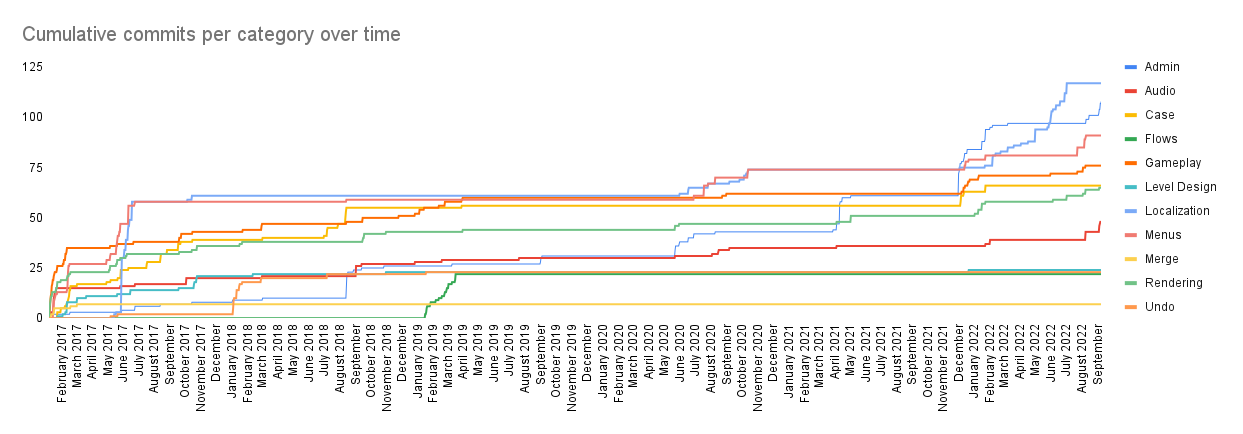

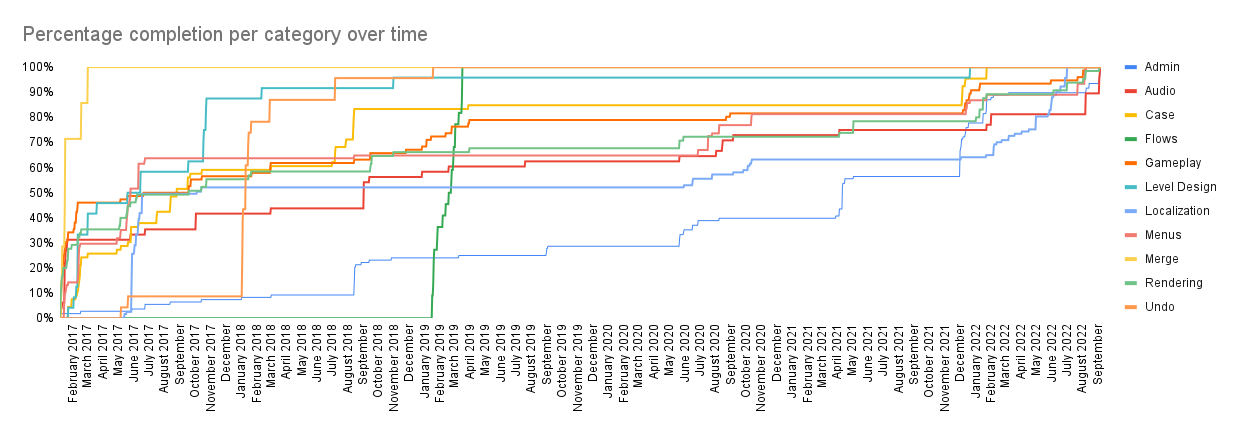

Here are a couple of variations on the cumulative commits graph from earlier. The first shows the cumulative commits for each category, you can see when each category was being worked on. There’s a lot of Admin at the end for example, when I was creating the itch store page.

And here is another variation, where the cumulative number of commits per category is divided by the total number of commits in that category, so they all go from 0 to 100%. Some categories like Flows or Undo were done in one big burst, while others like Menus were continuously revisited throughout the project.

Imaginary FAQ

OK you’ve explained why the game took so long, now why did this devlog take so long?

Go away :)

Will there be more devlogs?

Probably not!

What’s your next project?

Follow me on itch or Twitter to find out!

Thanks for reading, I hope you found it interesting. And if you haven’t already, please check out the game! Goodbye!

Curious Fishing

An aquatic puzzle game

| Status | Released |

| Author | RhythmLynx |

| Genre | Puzzle |

| Tags | blocks, chiptune, fantasy-console, Fishing, PICO-8, Pixel Art, Retro, Sokoban, underwater |

| Languages | Arabic, German, English, Spanish; Castilian, French, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese (Brazil), Russian, Chinese, Chinese (Simplified), Chinese (Traditional) |

| Accessibility | Configurable controls |

More posts

- #14: Devlog updates and launch statsNov 28, 2022

- #13: Release!Nov 28, 2022

- #12: Localizing a low resolution pixel art gameNov 28, 2022

- #11: OrganizationNov 27, 2022

- #10: Audio techNov 27, 2022

- #09: Interview with sound designer Andrew DoddsNov 27, 2022

- #08: (Work)flow: artNov 27, 2022

- #07: Design iteration: player movementNov 25, 2022

- #06: UndoNov 25, 2022

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.